Trimaxion Drone Ship

On our way to Data in Paradise in beautiful Santa Barbara, I’ve noticed that there were no seat-back TVs despite it being a newer plane. Since I don’t fly often, I wasn’t sure if this was related solely to American Airlines or a larger trend driven by the fact that most people today have entertainment devices in their pockets. “More than 90% of our passengers already bring a device or screen with them when they fly,” American Airlines said in a statement back in 2017. “Those phones and tablets are continually upgraded, they’re easy to use and, most importantly, they are the technology our customers have chosen.”

Joining the ranks of United and Alaska Airlines, American Airlines has decided to no longer install seat-back monitors for in-flight entertainment in its new domestic-bound Boeing 737s. Instead, the company is investing in its WiFi services to allow passengers to stream from Netflix and Amazon without the need to download movies or shows beforehand, and to enjoy free access to entertainment via their mobile phones, tablets, and laptops. While some aren’t happy with the recent changes, airlines are saving up to $10k per seat (not including maintenance costs) and passengers have more legroom as seat-back monitors come with in-flight entertainment boxes which take up at least 20% of under-seat space for aisle passengers.

Beware of amateurs

“You Press the Button, We Do the Rest” was an advertising slogan coined by George Eastman, the founder of Kodak, in 1888. Before Kodak became a household name, taking photographs was a complicated process that could only be accomplished if the photographer could process and develop film. Eastman believed that making the camera as convenient as the pencil will increase the number of photographers and he was right. Within a few years, snapshot photography became a national craze and kodaking, kodakers, kodakery entered common American speech. Kodak built an empire by making photography convenient for the masses, but when convenience is your main selling point you have to ask yourself if you’re good enough to stand alone when you lose your convenience edge.

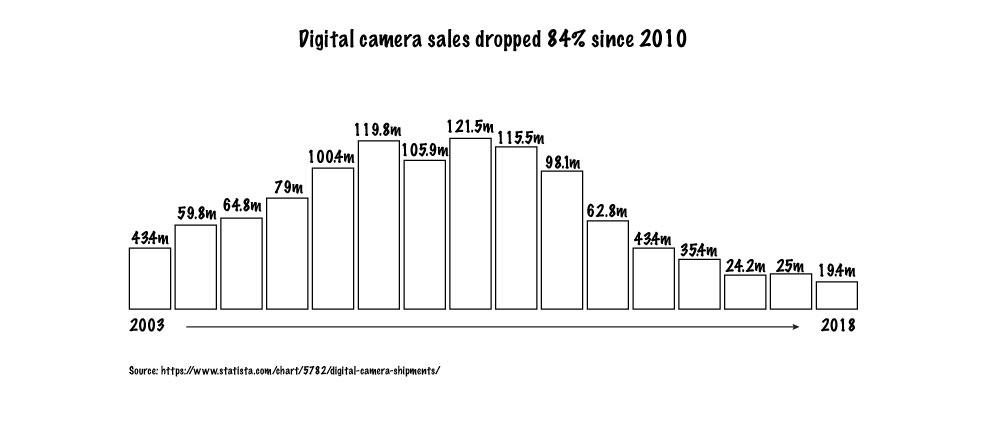

When Apple introduced the iPhone in 2007, some were skeptical. “The simple truth is that convergence [an all-in-one device] is a compromise driven by financial limitations, not aspiration. In the markets where multiple devices are affordable, the vast majority would prefer that to one device fits all,” said Tom Smith, Universal McCann’s research manager for Europe, the Middle East and Asia, following a comprehensive survey which predicted that the iPhone would struggle in rich markets, like the US, Europe, and Japan as few consumers wanted to trade in their cell phones, cameras, and MP3 players for an all-in-one device. But McCann was wrong – iPhone, in particular, and smartphones, in general, became popular while digital camera sales dropped 84% since 2010.

The smartphone replaced several standalone devices such as the camera, GPS and MP3. Obviously, the first iPhone didn’t have a clear picture like Sony’s digital camera. Having your phone as a navigation system isn’t ideal when you want to use it. And the sound quality of the first iPhone wasn’t as good as leading MP3s. But since the majority aren’t professional photographers, taxi drivers or die-hard Metalica fans, better prices and greater convenience are all you need, even when the quality isn’t as good. WeWork is another example. The company has members stacked like sardines but they are willing to pay the price because it’s a good price. But the biggest advantage of WeWork is also its biggest challenge. Unlike traditional offices that come with high rent and long-term lease commitments, WeWork made having an office a convenient and affordable option. This led many entrepreneurs that weren’t ready just yet to commit to a traditional lease to take advantage and graduate from their local coffee shops. But what will happen when WeWork increases its price due to its challenged business model? The amateurpreneurs will go right back to ordering cappuccinos and lattes.

Don’t get high on your own supply

Shefi used this saying in one of her slides at the conference. Working on our recent report Beyond Insurance – we wanted to illustrate the industry’s challenges and Tesla is the perfect example. Jaime Smedes is a New Yorker living in San Francisco who owns a Tesla Model 3, long-range AWD. Despite never doing so before, he felt obligated to name his Tesla so he chose Max, short for Trimaxion Drone Ship, the robotic commander sent to Earth to study humans in Disney’s 1986 Flight of the Navigator.

https://twitter.com/JaimeSmedes/status/1152656989891076096?s=20

As a technology enthusiast and a fan of Elon Musk, Jaime isn’t just loyal to the Tesla brand; he believes in its mission as well. He considers himself “pretty brand loyal,” admiring Apple and often choosing Nike since they’ve proven to stand behind their products over time. But while ‘brand’ is one word, its meaning varies.

David Ogilvy, the “Father of Advertising,” defined brand as the intangible sum of a product’s attributes. The Dictionary of Brand by Marty Neumeier defines brand as a person’s perception of a product, service, experience, or organization. And while there isn’t one unanimous definition, the benefit of a true brand is simply being able to charge a premium price for a similar or slightly better product or service. Chanel is a brand. Pappy Van Winkle is a brand. And although for some, Tesla is unlike traditional cars, most would argue that it serves the exact same purpose of taking you from point A to B so Tesla is also a brand.

On August 28, 2019, the Tesla brand was put to the test with a product from an industry that has no brands despite spending billions of dollars a year in advertising. The electric automaker announced the launch of Tesla Insurance in California to offer better rates for Tesla owners, but despite carrying the Tesla name, the insurance product didn’t morph into a premium product.

https://twitter.com/JaimeSmedes/status/1166820477626548225?s=20

Tesla owners still judged the product by its price, and so did Jaime. “Other than the possibility of Tesla insurance rates being lower than traditional insurers, I didn’t see any other value adds,” Jaime explains why he wasn’t willing to pay a higher rate. “For me, insurance is there as a backup plan. Hopefully, I’ll never need it, so why pay more for the same coverage?”

But Tesla does have an advantage over traditional insurance companies – it has engagement. Shortly after introducing the new insurance product and receiving several complaints about the high rates, Tesla announced on Twitter that it is making “some updates” regarding the product. Jaime, like many others who follow and engage with Tesla on social networks, noticed the update and went on to get another quote which made him leave Progressive behind. It was only when he received his proof of insurance card that he discovered the underwriter – State National – a company he never heard of. Finally, Jaime is willing to stick with the company as long as they are within 10% of the competition as he hopes that the premium will eventually drop over time in-line with the safety and overall costs of Tesla ownership.

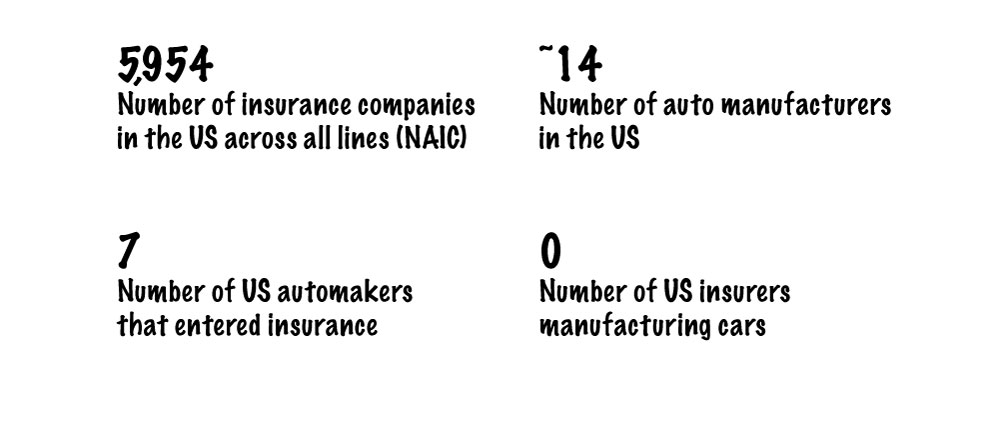

Before the Tesla announcement, in May 2019, Warren Buffett, chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, addressed Tesla’s plan to enter insurance: “It’s not an easy business,” Buffett told shareholders at the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting. “The success of the auto companies getting into the insurance business is probably as likely as the success of the insurance companies getting into the auto business.” Easy and hard are relative to one’s experiences and Buffett, who for the most part made his fortune by investing and acquiring companies, not by building them, is speaking from his own experience. On the other hand, Elon Musk is a builder. He built Zip2, the internet version of the yellow pages, which was acquired by Compaq for $307 million. He co-founded X.com, later PayPal, which was acquired by eBay for $1.5 billion. He created a car company from scratch, and he is behind the first private company to successfully launch and return a spacecraft from orbit. For Musk, entering insurance is as easy as finding a partner.

Enemies from within

Chances are that you’ve never heard of Evolve Bank & Trust. The 94-year-old bank is an enabler for some of the hottest fintech startups in town including Zero and Step. “We saw fintech coming down the pipeline, and really embraced it as another avenue for us to get deposits,” Evolve Bank chairman Scot Lenoir said in a recent interview with CNBC. “We decided from a strategic standpoint why not embrace that and collaborate with them?” And enabling these disruptors is sometimes your best bet; the bank’s fintech-related business is the fastest-growing by far, with more than 200% deposit growth month over month and almost no advertising spend. All of a sudden, a tiny bank can make waves and cause industry giants like Chase and Citi to respond.

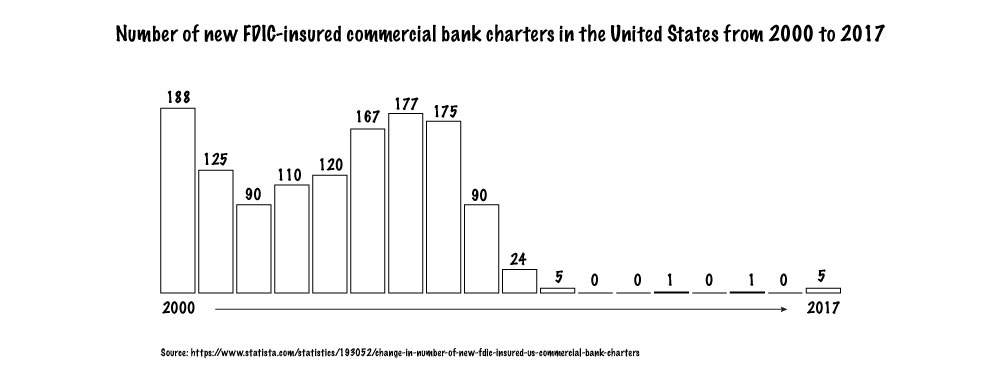

With similar characteristics to insurance (minus the usage), banks have realized that experience and expertise aren’t enough to protect them from outside threats. Luckily, new FDIC regulations made it harder to get a bank charter, resulting in a dramatic decline in recent years.

However, everybody wants to be the king in the kingdom, and small players with big dreams are opening the gates and disrupting the status quo. The same is happening in insurance. But unlike traditional banks that can transform themselves with better technology and millennial-style features, most insurance companies won’t be able to pull the same tricks. When you go back to the question above – whether you are good enough to stand alone – the answer is no. Insurance companies do not have the right to be consumer-facing with a mostly invisible product that’s driven by price. Tesla can save one or some of you if the price is right. Expedia can do the same even when offering a more expensive travel insurance product since it’s a one-time purchase. Nonetheless, in these scenarios, insurance companies are taking the backseat – a suitable place for a backup product. And now, to the ultimate question – will insurance companies be chosen by others or will they put themselves in a position to choose for themselves?

If it’s up to Buffett, he’ll be the one to choose.