The Ultimate Innovation

For the past several years, the term peer-to-peer (P2P) has been synonymous with the ultimate kind of innovation. Probably the most notable example is Bitcoin, which is described as an innovative payment network and a new kind of money that uses P2P technology to operate with no central authority or banks. And of course, we can’t forget about Lemonade, which claimed to be the world’s first P2P insurance company.

A term synonymous with P2P that’s trending today is decentralized. Peer-to-peer began to be used in reference to a system of computers that are able to communicate directly with one another without the mediation of a centralized server.

A term synonymous with decentralized that’s also trending today is web3. According to venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, the decentralized networks of web3 offer an alternative to the broken digital status quo:

“While centralization has helped billions of people get access to amazing technologies, many of which were free to use, it has also stifled innovation. Right now, companies that own networks have unilateral power over important questions like who gets network access, how revenue is divided, what features are supported, how user data is secured, and so on. That makes it harder for startups, creators, and other groups to grow their internet presence because they must worry about centralized platforms changing the rules and taking away their audiences or profits. The classic challenge of decentralized networks is that they are public goods. Without a central entity to control decisions and capture profits, it is hard to incentivize their maintenance and development. Crypto helps solve this problem through decentralized coordination and providing economic incentives for development. web3 will put power in the hands of communities rather than corporations.”

I’m no crypto or web3 pioneer, but I get the principle of decentralization, and if I had decentralization abilities, I’d go after food delivery apps first. The $20 meal I wanted to purchase via Uber Eats had a $3.99 delivery fee, $3.23 service fee, $0.45 fuel surcharge, and a recommended 18% tip ($5.42) based on the order amount, which included the various fees. With tax, $20 worth of menu items turned into a $33 expense. Of course, there’s a hidden tax — many restaurants charge different prices for orders sent through food delivery apps. My exact order would have cost $5 less if I had driven to this specific restaurant, which is essentially passing on some or all of the fees it’s being charged by food delivery apps to me.

Before discussing how to distribute food on the blockchain, it’s important to consider the other advantages of food delivery apps, like convenience and protection. With a few simple taps on the app, a customer who is having problems with an order can get it handled. Food delivery apps, speaking in terms of insurance, offer digital claims and quick payouts, but resolving an issue with food purchased straight from a restaurant will necessitate a phone call that may or may not result in some type of reimbursement related to the specific business.

The original decentralized method of ordering food in which consumers dealt directly with restaurants carried (and still carries) risk. The centralized solution of food delivery apps established a central authority to manage any disputes. In short, centralization works because it provides insurance and in order for decentralization to work, it will require insurance.

Offering a better product or providing higher value are the two basic ways for a company to acquire customers. Some claim that Tesla produced a better car, allowing them to charge a higher price for their vehicles. Amazon, on the other hand, is known for giving excellent value through fast and free shipping as well as simple returns. When we look at the P2P/decentralized/web3 movements in terms of better product/higher value, we see that they are first and foremost driven by people’s desire to capture more value.

This week, P2P carsharing marketplace Getaround announced its intentions to go public via a SPAC merger. The company helped hosts – those renting their cars – earn $370M as of December 31, 2021. Getaround, and others in the space, gave car owners a revenue stream that was once reserved only for car rental companies. On the negative side, Getaround is not a true P2P company – it’s a centralized service run by a corporation. However, P2P is about value and value is subjective.

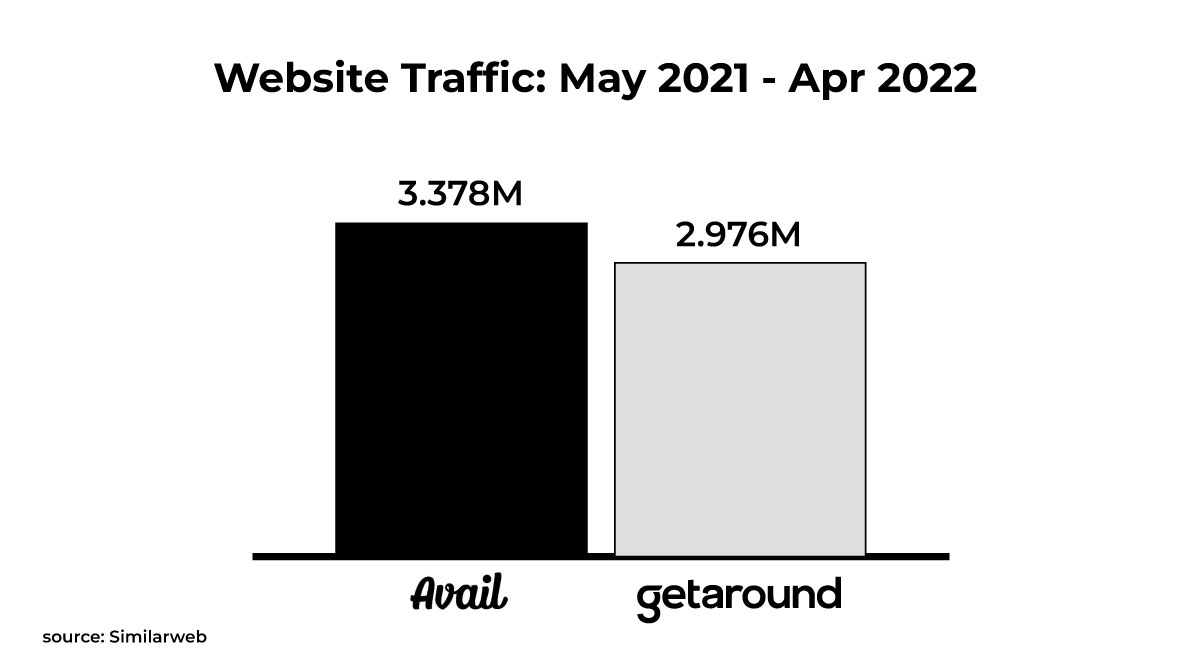

Getaround established a new program last year to assist customers who wish to rent out more than a few cars. Clearly, this is intended to help hosts earn more money, which means more money for Getaround. Allstate’s carsharing company Avail, on the other hand, was created to lower the expenses of car ownership. Judging purely by website traffic numbers, Avail is a contender – it generated more traffic in the U.S. than Getaround.

Carsharing on a P2P basis is a tricky business. It’s something Getaround has been doing since 2011 without turning a profit. Tom Wilson, the CEO of Allstate, admitted this truth as well. “The challenge for us [is] in making money,” he said in 2020. “All the research shows we can make money in it. I think the biggest challenge is an operational one. This is math. We are moving cars around, people around, getting them clean, people spilling Diet Cokes in the front seat, leaving something in the back seat.” Of course, Wilson left out additional incidents like car damage and theft, which Avail and other P2P carsharing platforms continue to deal with.

Assuming the original mission hasn’t changed, Allstate looking to reduce the cost of car ownership by helping owners monetize their cars is a smart move. It’s also wise to leverage this network to reduce car rental costs according to Wilson: “We buy over $0.25 billion of rental cars a year for our customers, so wouldn’t it be nice if we could shift some of that money to our customers as opposed to the big rental car companies?”

But what if Allstate is overlooking something important? Getaround’s main business is the fee it charges hosts to rent out their cars. Allstate’s main business is insurance, not carsharing. And since the benefit of centralization is insurance, what if insurance companies could bring insurance to an environment that would provide greater value for individuals? For example, a P2P (policyholder-to-policyholder) insured marketplace for renting cars, borrowing equipment, storing items, or finding a dog sitter without the higher costs associated with centralized platforms. One main element of P2P is numbers – Spanish P2P insurance startup Cobertoo failed to build a large community👇. Companies like Allstate, State Farm, Progressive, GEICO, and even Lemonade have the numbers to build P2P networks that can provide value to their policyholders, and imagine how bigger they could get if one insurance company opted to collaborate with another.