The History of Health Insurance: Past, Present, and Future

Health insurance (officially called “accident or health and sickness”) is one of the major, or general, lines of authority (LOAs) defined by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) in its Uniform Licensing Standards (ULS).

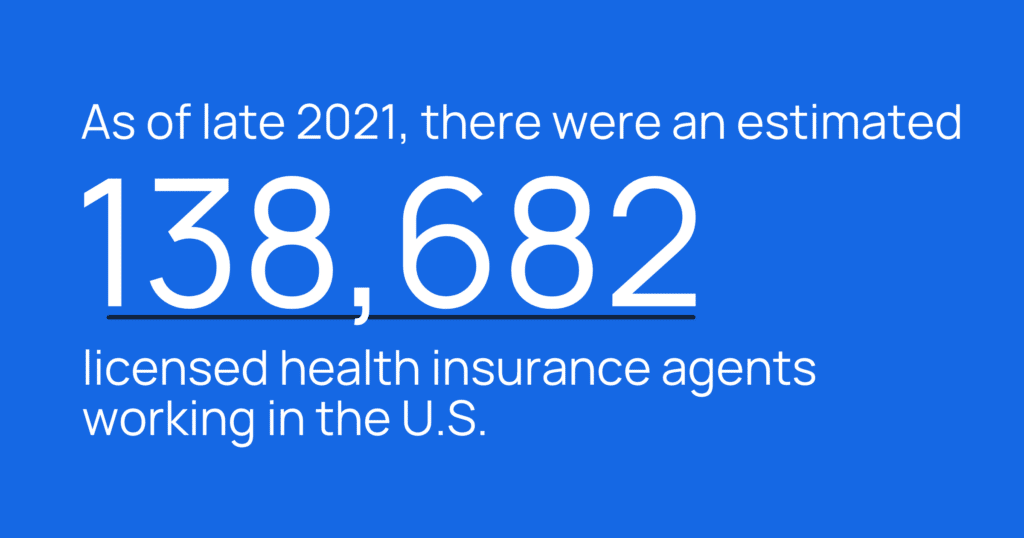

As of late 2021, there were an estimated 138,682 licensed health insurance agents working in the U.S. The Insurance Information Institute (III) also reports that in 2021 life and health insurance carriers employed over 900,000 people. That’s compared to just over 600,000 people that the III reports carriers employed for property and casualty insurance.

Any way you slice it, selling benefits is a big business in the U.S. Between insurance carriers and insurance agencies, brokers, MGAs, MGUs, and any other acronymous entities we’ve forgotten, over a million people play a role in getting these vital insurance products to the nation’s population. Given health benefits are such a large part of the insurance industry, we thought it would be good to take a deeper dive into their history, current state, and potential future.

While compliance is normally our jam, this blog will focus more on history. If you’re jonesing for some regulatory action, check out our previous series on the who, what, and how of health insurance compliance for employers, health insurance carriers, and health insurance agencies and brokers. On the other hand, if you want to skip to the good part and just simplify your producer onboarding and license compliance management, see how AgentSync can help.

Part 1: The history of health insurance in the U.S.

The first health insurance

Health insurance resembling what we think of today began in the 1930s during the Great Depression. Prior to that, it wasn’t so much “health insurance” to pay for the costs of medical treatment, rather it was what we would today call disability income insurance.

Because medical technology wasn’t very advanced, the actual cost of obtaining healthcare was relatively low. Prior to the 1920s, most surgeries were performed in people’s own homes, so hospital bills were rare. People were more concerned about the wages they’d miss out on if they were sick and unable to work. For this reason, “sickness insurance” products started popping up to help people cover their living expenses when they couldn’t earn an income due to illness or injury.

Another early form of health insurance is what was known as a “sickness fund.” These funds were either set up by banks that would pay cash to members for their medical care or, in the case of industrial sickness funds, started by employers to benefit employees. Sickness funds arranged by financial institutions came first (around the 1880s), followed by industrial sickness funds, which remained popular throughout the 1920s. The concept of an industrial sickness fund also played a role in the labor movement and, later, healthcare through unionization.

Early workers’ compensation insurance

Health insurance has been tied to employment for much of its history in the U.S., perhaps not surprisingly because jobs were historically dangerous and were some of the most common ways to get injured before the days of cars, mass transit, and airplanes.

In the early 20th century, employers were legally obligated to pay for medical care when an employee suffered an on-the-job injury, if the employer was negligent. However, there were three ways an employer could be absolved of their duty:

- Claim the worker had taken on the risk as part of employment

- Claim the injury was due to another worker’s negligence, not the company

- Claim the injured employee was at least partially responsible for the accident

Around this time, workers’ rights movements were gaining momentum and states were making new laws to reform child labor, limit the length of the work week, and deal with the common occurance of workplace injuries and the lawsuits that came with them. Hence, the birth of workers’ compensation laws. Worker’s rights activists advocated for new laws as a way to put the financial responsibility of injured workers onto employers instead of employees. At the same time, employers found the laws would allow them to care for injured workers at a lower overall cost, without the frequent court cases.

The first federal law resembling workers’ compensation came in 1908 when Congress passed the Federal Employers Liability Act (FELA). This law only applied to railroad and interstate commerce employees, and only paid if an employer was found to be at least partially responsible for the accident. However when it did pay, the benefits were larger than contemporary workers’ compensation insurance.

Between 1910 and 1915, 32 states passed workers’ compensation insurance laws that allowed employers to buy insurance through the state. While not mandatory (as it is today in most states), employers that purchased workers’ compensation insurance through their state could avoid civil liability for the accident, while still providing healthcare and compensation to the injured employee and spending less money fighting their case in court.

The first fights for universal healthcare in America

By the 1920s, many European countries had developed some form of nationalized healthcare for their citizens. In the U.S., a movement for the same was active during the early decades of the 20th century, yet failed to take hold. Researchers attribute the failure of nationalized healthcare in the U.S. to a variety of reasons, including:

- American physicians, represented by the American Medical Association (AMA) opposed “compulsory nationalized healthcare.” This is in large part due to what doctors saw when workers’ compensation started to take hold. That is, to control costs, employers contracted with their own physicians to treat on-the-job injuries, which negatively impacted business for the family physicians. Doctors at large feared this type of trend would lead to the inability to set their own fees, should health insurance become universal across the country.

- Sickness funds, “established by employers, unions, and fraternal organizations” served the needs of as many as 30 to 40 percent of non-agricultural workers employed in America. With these funds in place, providing the type of benefits Americans felt was most needed (salary replacement, not healthcare), sickness funds and those supporting them proved to be a powerful lobbying group against universal healthcare.

- By the 1930s, commercial health insurance had begun gaining traction. More on this below, but commercial insurance plans didn’t like the idea of a government healthcare system.

Universal, or compulsory, nationalized healthcare has been a topic of debate in the U.S. for over a hundred years now. The idea’s been posed and supported by presidents ranging from Theodore Roosevelt to Franklin Delano Roosevelt to Harry Truman. Yet, each time, legislation has been soundly defeated thanks to political lobbying by everyone from the AMA to sickness funds to the modern health insurance industry.

The start of commercial health insurance and employer-sponsored health plans

Before there was Blue Cross Blue Shield, United Healthcare, or CIGNA, there was a group of school teachers in Dallas who joined forces with Baylor University Hospital to “prepay” for their healthcare at a premium of 50 cents per person, per month. This model is largely referenced as the first modern commercial hospital insurance plan, and evolved directly into an organization you may have heard of called Blue Cross. In return for paying 50 cents per teacher, per month, school systems were guaranteed their teachers could spend up to 21 days in the hospital at no cost. As you can imagine, the number of teachers who actually needed to stay in the hospital would be much lower than the number paying into the plan, thus making it financially viable for the hospital to uphold its end of the bargain.

This new model came about largely due to the start of The Great Depression. Baylor University Hospital, for example, saw its monthly income drop dramatically as fewer patients could pay and more relied on “charity care.” In an effort to give hospitals a consistent cash flow, Justin Kimble (Baylor University Hospital Administrator) came up with the idea to have “members,” or (more likely) their employers, “prepay” for services via a small monthly premium.

Plans like this one caught on across the country. Soon, employers weren’t just making deals with one particular hospital, but with a geographically clustered group of hospitals that turned to the American Hospital Association (AHA) for guidance on which deals to accept or reject.

It’s important to note that these early forms of health insurance didn’t include physicians, by design. Physicians, guided by the AMA, refused to be a part of this particular system because they didn’t believe it would serve their interests. Thinking back to early workers’ compensation plans, physicians believed that most of them would be cut out of providing care in favor of a select few, and that involving any type of third party would impact their ability to charge reasonable fees for their services. So, they formed their own association in response: Blue Shield.

The idea behind Blue Shield was to preemptively organize around primary care so that the Blue Cross model couldn’t impose itself on family physicians. At the same time, physicians saw that Blue Cross hospital coverage was becoming more popular, and that universal healthcare was back in political discussions. They decided it was better to organize into their own association of healthcare plans rather than risk either the AHA-backed Blue Cross or the U.S. government doing it for them.

While Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans claimed to be prepaid care and not insurance plans, the New York state insurance commissioner begged to differ. In 1933, New York determined that they were insurance plans, similar to life insurance and P&C. This meant insurance regulations now applied to Blue Cross and Blue Shield, although the state legislature created some new laws allowing the Blues some leeway as nonprofits rather than for-profit insurance companies.

Separately, although certainly inspired by the formation of Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans across the country, the insurance company that would later be known as Kaiser Permanente had similar origins to the Baylor University Hospital arrangement. In 1941, Henry J. Kaiser partnered with Dr. Sidney R. Garfield to create prepaid healthcare for his shipyard workforce. In 1945, the Kaiser Permanente Health Plan was officially founded and soon spread across the state of California and beyond. During the height of World War II, when demand for their labor was at its peak, the Kaiser “shipyard” health plan covered over 190,000 people in the states of California, Washington, and Oregon.

The growth of commercial insurance and employer-sponsored health plans

By the 1940s, health insurance plans were becoming more commonplace. But at the start of the decade, they still hadn’t turned into the major component of employee compensation they are today. In fact, while it’s hard to truly quantify, researchers estimate about 9 percent of the U.S. population had “some form of private health insurance” in 1940.

This all changed in 1943, thanks to a decision by the War Labor Board, which declared benefits (like health insurance) that employers provide for their employees do not count as “wages.” This is significant because there were government-imposed wage caps, and price caps on nearly everything, in an attempt to stave off wartime inflation. During World War II, the labor market was tight and companies – desperate to keep production moving for the war effort and everyday civilian needs – competed for workers but couldn’t raise wages to help their recruitment efforts. But if health insurance wasn’t considered “wages,” voila!

Employers began offering health insurance plans to give workers extra money in their pockets without raising wages (and breaking laws). This, combined with a growing number of unionized employees and new, favorable tax laws that made employer-sponsored healthcare non-taxable, made the 1940s and 1950s a period of extreme growth for health insurance. By 1960, over 68 percent of the U.S. population was estimated to have some form of private health insurance: an astronomical growth from the 1940 numbers.

Medicare and Medicaid address gaps in commercial insurance

With commercial (and nonprofit) health insurance companies now fully embedded into American culture and employment practices, a new problem arose. What about healthcare for older Americans who retire from their employer? The issue wasn’t entirely about retirement, either.

In the early stages of health insurance, everyone paid the same premium regardless of how risky they were as an individual: a practice known as “community rating.” As competition between insurers grew, insurance companies realized they could give better premiums to lower-risk groups of people. Younger, healthier, and less likely to get injured people: teachers, for example. You don’t need a degree in actuarial sciences to conclude that the health risks teachers face are significantly less than those coal miners face, as an example.

As organized labor unions also grew in popularity, insurance companies could win contracts with desirable professional unions by offering “experience-based rates.” Ultimately, market pressure forced all insurers to go that direction or else face losing all customers except the most high-risk, which doesn’t make for a successful insurance company! As insurance companies largely moved from community rating to experience rating, the result was lower premiums for people less likely to incur claims (again, teachers were a pretty safe bet) and higher premiums for people who were more likely to incur claims: i.e. the elderly.

While experience-based rating worked well for insurance companies, and for people in their working years, it was decidedly not great for the elderly, retired people, and those with disabilities. The most vulnerable populations were left paying the highest premiums. That’s why in 1965 (although the groundwork was laid much earlier) President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Medicare into law.

Fun fact: Part of the reason Medicare is so complicated and contains so many different parts goes back to appeasing the interests of the different groups that each had a stake at the table. If you remember, the AHA (which supported those early Blue Cross insurance plans that provided steady income to hospitals during the Great Depression) backed what would become Medicare Part A: Hospital coverage. Alternately, the AMA (representing physician’s interests, who were not so much in favor of universal coverage) became Medicare Part B: Voluntary outpatient physician coverage.

The third layer of the Medicare “layer cake” (no joke) was expanding federal funding to states that helped cover low-income elderly and disabled people. And just like that, Medicaid was born. While Medicaid was signed into law by President Johnson in 1965 as part of the Medicare law, it was really left to the states to decide how to use that money, so the application of Medicaid was (and still is today) patchy across state lines.

For more on Medicare from the AgentSync blog, check out our Medicare 101 content, read up on the state of Medicare Advantage, find commentary on the role of digital transformation in Medicare, or catch up on best practices for managing your producer workforce before and after Medicare Open Enrollment season.

The rise of managed care: HMO, PPO, and POS plans

In the history of health insurance, everything old is new again. As healthcare costs continued to rise – thanks to advances in medical technology, among other factors – insurance companies looked for ways to control those costs.

Taking a lesson from some of the first health insurance plans, they decided to manage care by creating provider networks. And, just like the very first health plan where a Dallas school system “prepaid” care for their teachers (but only if they got it at Baylor University Hospital!), insurance companies started setting up specific hospitals that members could go to and receive covered services.

HMO plans

Health maintenance organizations (HMOs) are the most limiting version of managed care. While there are several different types of HMOs, the basic premise is that members can only get care from specific providers – assuming they don’t want to pay full price out of pocket! When you’re enrolled in an HMO plan, you’re limited to a specific network of doctors, hospitals, and pharmacies. Your health plan pays these providers according to agreed-upon fees, and it doesn’t have to worry about “what if it costs more.” It won’t: That’s part of the HMO agreement.

Oftentimes HMO plans also include cost-containing measures such as requiring people to visit a primary care physician before seeing a specialist. The theory is, people may believe they need a specialist (read: more expensive care) when in fact their primary care doctor would be capable of handling the concern.

PPO plans

Preferred provider organizations (PPOs) started popping up in the 1980s after the enactment of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). As employers started to self-insure, thanks to the newfound freedom from state-by-state insurance regulations that ERISA afforded them, the HMO model didn’t work as well.

PPOs, rather than being insurers themselves (as was mostly the case with HMOs), were more like contract coordinators. PPOs help with logistics between providers and insurance plans (whether fully insured or self-funded). In the case of fully insured health plans, the insurance company uses the PPO model itself, the same as a self-insured employer would, even though they aren’t an insurance company.

PPO plans have become a popular option for group and individual health insurance over the last 40 years, as they afford consumers more choice over where to go for their care. Typically, PPO networks are broader than HMOs. Plan members are still limited to coverage at participating providers, but it’s not the same level of limitation as an HMO.

POS plans

Despite an unfortunate acronym, POS doesn’t stand for what you might think. Point of service plans are a mix of some HMO features and some PPO features. The key is that members get to choose who they want to see, and how much they want to pay, at the “point of service.” A POS plan is basically an HMO’s answer to the freedom of choice consumers get with a PPO. They offer members the option to pay more to see non-participating providers, or to keep their own costs lower by sticking with the HMO’s own panel of providers.

Having laid out these three types of managed care plans, it’s important to realize that there are other types of plans, and even within these, nuances can create large variations for plan members. The whole thing can be confusing to employers, plan members, doctors, and patients alike. Thankfully, those responsible for selling health insurance to the masses are required to be licensed to do so, which comes along with a lot of educational requirements, for which this blog is not a substitute, despite its substantial length.

Part 2: The Current State of Health Insurance Benefits in the U.S.

Health insurance and other related benefits aren’t everyone’s favorite topic of conversation. Luckily, we’re insurance nerds. So, if you’re looking to explore what’s happening in the state of U.S. health insurance, you’ve come to the right place. Read on to explore a time period that we’re loosely calling “the present.” In reality, we’ll revisit the 1990s through today (the 2020s).

While much has changed over the past 30 years, in large part because of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), a lot of the challenges related to health insurance benefits in America remain the same, if only more visible and painful. As we talk about the current state of health benefits in the U.S., we’ll cover the success and failures of the system as it evolved from its earliest days into what it is today.

Where do Americans get their health insurance?

According to the 2020 U.S. Census, more Americans get their health insurance through private, employer-sponsored coverage than through any other single source. Medicare comes in second place, followed by Medicaid, and then various other private-purchase and government options.

And then there’s a large chunk of people who don’t have insurance at all. Among the U.S. population (332 million in 2022) 31.6 million people, or 9.7 percent of the country, remain uninsured. While this number is undoubtedly high, it’s actually an improvement over decades past. The reduction in uninsured Americans is at least in part due to healthcare reform efforts, which comprise much of the history of present-day benefits in America.

A crisis of uninsured Americans

By the year 1991, a two-pronged problem had emerged: rising healthcare costs and a growing number of uninsured Americans. This issue should sound familiar to most, if not all, of our readers. Afterall, you can’t swing a squirrel these days without hearing about “rising healthcare costs.” But it might surprise you to learn that the cost of healthcare, including a lack of access to affordable health insurance coverage, was a documented problem as far back as 1980, if not earlier!

In a 1992, a study that examined the monthly U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Surveys (CPS) between 1980 and 1991 found:

- Income was the “single most important factor” for families in deciding whether to purchase health insurance or not (aside from the elderly population who were nearly universally covered by Medicare).

- Children in families who made too much money to qualify for Medicaid but not enough money to purchase health insurance were the most likely to be uninsured.

- In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the workforce shifted toward service industry jobs, which were less likely to provide insurance even to full-time employees who worked year round.

- There were significant regional differences (many of which still hold true today) in how much of the population was insured.

All in all, more than 34 million people (about 13 percent of the population) were uninsured in 1991. This seemed like a lot to researchers at the time, but the numbers only grew over the next 20 years. In 2006, 47 million Americans (15.8 percent of the population) were uninsured. In 2010, this number rose to 48.6 million people (16 percent of the entire population). In this context, 2022 numbers don’t seem nearly as bad.

The rising cost of healthcare in the U.S.

Without health insurance coverage, millions of Americans were, and are, left to pay for their healthcare out of pocket. While this might have been manageable in the early 20th century, advances in medical technology, general inflationary factors, corporate greed in the form of growing biotech and pharmaceutical profit margins, and high healthcare administrative costs (among many other factors) drove the price of care upward. No longer is a doctor setting their neighbor’s broken leg with a stick and belt, and a summer’s growth of carrots as payment.

As a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), medical spending in the U.S. nearly quadrupled from 5 percent in 1960 to almost 20 percent in 2020. Not only has the percentage of GDP we spend on healthcare risen dramatically, but it’s worth noting that GDP itself has skyrocketed since 1960 – meaning the actual increase in dollars spent on healthcare is mind-bogglingly high compared to what it was in the middle of the last century.

Even after adjusting for inflation over the course of decades, healthcare spending still increased by almost twice as much (5.5 percent) as spending on other areas of the U.S. economy (3.1 percent) between 1960 and 2013.

With this backdrop, it’s no wonder that medical professionals, regular Americans, and politicians alike were and are all searching for a solution to both the cost of healthcare, and the affordability and availability of health insurance coverage.

Early attempts at healthcare reform

In Part One of our History of Benefits series, we covered the earliest formation of what could be considered health insurance in America, along with a few of the earliest attempts to make it universally available. Needless to say, those attempts didn’t succeed. Outside of the massive achievement that was creating Medicare and Medicaid, most Americans were left with limited options, high insurance premiums, and coverage that could be limited and dictated by insurers looking out for their bottom line.

As we moved into the late 20th century, there are a couple of notable instances of healthcare reforms that tried to revolutionize the way Americans get and pay for medical treatment.

The Clinton healthcare plan of 1992

Before there was Obamacare, there was Hillarycare. Alas, despite its potentially catchy name, this attempt at healthcare reform wasn’t meant to be. When Bill Clinton campaigned for president in 1992, one of his major campaign platforms was making healthcare more affordable and accessible to regular Americans. He ambitiously aimed to have healthcare overhaul legislation passed within his first 100 days in office. Spoiler alert: It didn’t work.

Clinton introduced the Health Security Act to a joint session of Congress on Sept. 22, 1993. And for an entire year, Congress did what it often does best: nothing. The bill was declared dead on Sept. 26, 1994. If it had passed, Clinton’s Health Security Act would have been revolutionary. It called for universal coverage for every American, along with mandating that employers pay 80 percent of the average cost of each employee’s health plan. Along with that, the bill would have provided government assistance for health plans at small businesses and for those that were unemployed or self-employed. The act also included the addition of mental health and substance abuse coverage into health plans.

Although it didn’t pass into law at the time, many of the concepts within Clinton’s Health Security Act resurfaced in future healthcare reform attempts.

Romneycare in Massachusetts

Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney unwittingly laid the foundation for future federal legislation when in 2006 he signed state healthcare reform into law. Although it was known as “Romneycare,” the Democrat-controlled legislature overrode Romney’s vetoes that attempted to remove key provisions from the law.

Thus, thanks in part to Romney, but in even larger part to his opposition-party state house and senate, Massachusetts became the first state in the U.S. to achieve nearly universal healthcare.

This Massachusetts healthcare law did a few things that may sound familiar to those who know the ins-and-outs of the Affordable Care Act.

- The law required all residents of Massachusetts over the age of 18 to obtain health insurance (with some limited exceptions).

- The law mandated that employers with more than 10 employees provide health insurance benefits to employees or face financial penalties.

- It provided subsidies for those who didn’t qualify for employer-sponsored health insurance coverage to make purchasing individual policies affordable.

- It established a statewide agency to help people find affordable health insurance plans.

With Massachusetts’ healthcare reform law signed, the state of Vermont and the city of San Francisco soon followed suit with their own nearly universal healthcare legislation. Romneycare proved to be successful, at least by some measures such as reduced mortality. At the very least, it demonstrated that achieving almost universal coverage was possible, albeit on a small scale.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA)

The PPACA, commonly known as the ACA, and even more casually as “Obamacare” was the largest change to the healthcare system since the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid. After his historic election in 2008, President Barack Obama used his Democratic control of the U.S. house and senate to do something no other president ever had. With a slim majority, the ACA passed in the U.S. House of Representatives by a margin of only five votes. It then went on to pass in the Senate with the bare minimum of 60 votes needed to avoid a filibuster.

Despite having to sacrifice some of the more progressive pieces of the ACA (like a public option for universal coverage), the fact that it passed at all was a major win for Democrats and anyone who hoped to see the U.S. healthcare system become more friendly to consumers. With the passing of the ACA, many widely popular new provisions came about to protect patients from “the worst insurance company abuses.”

What did Obamacare do?

The ACA, or Obamacare, put laws into place to guarantee minimum levels of coverage, along with maximum costs, for any insured American. At least, those who were insured by an ACA-compliant plan. Even after the enactment of the ACA, plans could be considered “grandfathered” and keep their noncompliant policies as long as an insurer continued to offer them since before March 23, 2010, without interruption.

Some of the most well-known and most popular provisions of the Affordable Care Act include:

- Prohibiting health insurance plans from denying people coverage because of pre-existing conditions

- Removing annual and lifetime limits on the health benefits provided

- Allowing young adults to remain on their parents’ health insurance until age 26

- Requiring health plans to cover most preventive care services without any cost to the plan member

Attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act

Despite all the good it did, some provisions of the ACA were unpopular among ordinary Americans as well as politicians. The “individual mandate” and tax penalties for not having creditable coverage every month of the year are just a couple of the law’s opponents’ chief complaints. Despite the American public’s mixed emotions about the entire ACA (not to mention confusion over whether the ACA and Obamacare were one and the same) the law has proven impossible for Republicans to repeal.

In 2019, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the individual mandate, ruling that it was unconstitutional. But in June 2021, the court threw out a lawsuit from states trying to argue the entire ACA was invalid without the individual mandate. Despite many Republican politicians’ best efforts, aspects of the Affordable Care Act like the ban on pre-existing condition limits have proven too popular to get rid of. After all, no one wants to be the person to take insurance away from 24 million Americans, which was just one likely outcome of repealing the ACA.

There’s no question that the ACA has shifted the landscape of healthcare and benefits in America since 2010. So much so, that we can’t possibly do justice to it in this blog. For a comprehensive deep dive into all things ACA, this is a great resource.

The post-Obamacare present

In 2022, we’ve been living with the Affordable Care Act for 12 years. It appears the law is here to stay and, in fact, recent legislation such as the 2021 CARE Act and 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act have only served to strengthen it.

Still, we’ve ticked back up from the 2016 all-time low of “only” 28.6 million uninsured Americans. This is a long way from the dream of universally available and affordable healthcare. The idea of “Medicare for all” continues to play a large role in our elections and public rhetoric, yet the reality of achieving a single-payer system seems outlandish given our current hyper-partisan political climate.

Part 3: The Future of Health Insurance Benefits in the U.S.

As of mid-2022, the most recent data available from the U.S. Census Bureau shows that most Americans (66.5 percent total) got health insurance coverage through their employer or another private source for at least part of the year (in 2020). Meanwhile, 34.8 percent of Americans with health insurance got their benefits through a public program like Medicare, Medicaid, or Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) benefits, etc.

Until there’s a public health insurance option for all Americans, or universal compulsory healthcare in America, chances are good that employer-sponsored health insurance benefits will remain the leading single source of health insurance benefits in the U.S. That also means, with health insurance still largely tied to employment, trends impacting the labor market such as The Great Resignation and The Great Reshuffle will also impact Americans’ access to health insurance benefits.

The current system is far from perfect. In fact, it’s faced many of the same challenges – from rising costs to lack of access – for at least the last 50 years (as we discuss in Part Two of this series).

Without a crystal ball, we can’t predict the future of how health insurance will evolve to meet these challenges, or not evolve and keep facing the same issues for another 50 years. However, in part three of our History of Benefits series, we’ll lay out some of the up-and-coming considerations the healthcare industry has and potential solutions, including how technology can help.

New challenges to an old health insurance system

As we mentioned, some of today’s top healthcare challenges have existed for at least half a century. Rising healthcare costs and a growing uninsured population aren’t new. There are, however, a couple of challenges that are uniquely 21st century in nature.

Digital natives want digital-first healthcare experiences

Digital natives, a term coined by author Marc Prensky in 2001, refers to those born roughly after 1980 (and even more so, closer to the year 2000). This generation was the first to be born into the digital age of computers, the internet, cell phones, and video games.

Referring to students, Prensky wrote, “It is now clear that as a result of this ubiquitous environment and the sheer volume of their interaction with it, today’s [digital natives] think and process information fundamentally differently from their predecessors.” This holds true outside the classroom as well. And, if Prensky thought the generation of students in 2001 processed information differently from those before them, you can only imagine how much more this is the case 20 years later.

In 2022, anyone under the age of 43 is likely to be a digital native, assuming they grew up in a typical American household that possessed common technology of the day. This group happens to overlap with the largest segment of the U.S. workforce: According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics there are over 91 million people aged 18 to 45 currently in the labor force. This means the largest chunk of working Americans are digital natives and therefore expect a different kind of experience when it comes to everything, including their healthcare.

A 2018 study found that undergraduate students, age 18 to 21, significantly preferred interacting with their healthcare system via email, online portals, and text messaging for mundane tasks like booking appointments and receiving test results. The same study found they overwhelmingly preferred a face-to-face doctor’s visit over a phone or web appointment – though we should note this was pre-COVID-19, and the acceptance of telehealth has increased dramatically in recent years.

More than a specific method of receiving care, the “second generation digital natives” in the study expressed a strong preference for choice and convenience in their healthcare services. This shouldn’t be surprising for those who’ve grown up with the internet in the palms of their hands. Given the typically narrow choices and low levels of convenience in the current U.S. healthcare system, including health insurance options largely offered through employers, it’s not surprising that improving the patient/consumer experience is what today’s digital healthcare disruptors are focused on.

Millennials would benefit from healthcare that wasn’t tied to employment

Without trying to sound like a broken record: The COVID-19 pandemic changed everything, and accelerated trends that were set into motion long before 2019. Even before the pandemic, research confirmed that millennials, now the largest faction of the U.S. workforce, quit their jobs at a rate three times higher than other generations.

When health insurance benefits are tied to employment, quitting a job can have significant financial and health consequences for employees and their families. Things like having to meet a new deductible mid-year and having to change providers or provider networks can seriously impact people’s access to care. For a generation that wants to be mobile, and for whom it’s often been necessary to “job hop” to achieve better pay, decoupling health insurance from employment would be a huge benefit – as long as employees still have a means of accessing affordable healthcare outside of their employer.

New alternatives to traditional health insurance models

The way most Americans get their health insurance has remained largely the same over the past 80 years, with more than 156 million people accessing it through their employers in 2021. For reasons we’ve previously outlined, this may not be an ideal direction for healthcare to keep going as the demands and expectations of future generations shift. And, of course, considering the issues of affordability and access under the current system remain long term challenges.

Luckily, some alternatives have begun to emerge. Although some are better than others, the following are some of the most prevalent new(er) options for consumers.

Defined-contribution models

Similar to traditional employer-sponsored healthcare, a defined-contribution healthcare plan consists of an employer putting money toward the cost of employees’ healthcare premiums. Where defined-contribution health plans differ from traditional employer-sponsored health plans is in the framing of the benefit.

With a defined-contribution healthcare plan, the employer chooses a fixed dollar amount that each employee receives to put toward the cost of their medical needs. The employee can then choose to spend that money (plus some of their own money) on the health insurance plan they choose. This can include plans designed by the employer, private exchanges, or purchasing a health plan on the marketplace.

The end result may be the same – for example, an employer covering 80 percent of monthly premiums – but employees may view the benefit more favorably when they see exactly how much their employer is contributing. Defined-contribution health plans also give employees more options on which plan to purchase than what’s typically presented in an employer-sponsored group health plan. It also may mean an employee can keep their health plan even if they leave their job, if they’ve been using their defined contribution to purchase a plan on their state’s healthcare exchange.

Healthshare ministries

Big, fat disclaimer: Healthcare sharing ministries are not health insurance! They are, however, a model that’s emerged and grown more popular in recent years as people search for alternatives to employer-sponsored health insurance.

The basic idea of a healthshare ministry, which is often sponsored by a religious organization, is that members pay monthly dues that are then used to reimburse other members for healthcare needs. It’s a similar idea to a self-funded health plan, except it’s not. Because healthshare ministries aren’t classified as insurance, they operate outside of state and federal insurance regulations. This can cause some issues.

We at AgentSync are in no way endorsing healthshare ministries as an alternative to a health insurance plan, but we have to acknowledge they’re out there and, as evidenced by their popularity, some people do see them as an alternative approach to the quagmire of the traditional health insurance system.

Onsite workplace health clinics

In an effort to control costs, perhaps by encouraging prevention and early detection of serious conditions, some employers are turning to onsite clinics for employees and their dependents. Often, such onsite clinics are free of charge and don’t require insurance at all.

The convenience and cost of these workplace clinics can help boost utilization of primary care and preventive services. Larger employers can realize even more cost-savings by reducing the number of health and wellness vendors they need without reducing the types of benefits their employees can access. By staffing the clinic themselves, or contracting with a third-party, employers can cut out the excessive administrative costs associated with health insurance for a large portion of their employees’ routine medical needs.

Direct primary care

Direct primary care (DPC) is a relatively new method for people to obtain healthcare. It emerged in the mid-2000s and seems to be growing more popular as people and employers seek ways to contain healthcare costs.

Just like it sounds, the DPC model is based on a direct relationship between doctors and patients without involving health insurance companies. In this model, consumers (or employers, if they choose to offer this type of benefit) pay a monthly fee to their primary care practice and receive benefits like unlimited office visits and discounts on related services like labs and imaging. By accepting payment directly from their patients, physicians have been able to reduce the administrative costs associated with accepting insurance and provide more personal attention to patients at a lower overall cost.

It’s important to understand that DPC memberships don’t help cover the costs of things that traditional insurance plans do. Things like hospitalization, emergency room visits, advanced imaging, and anything that typically takes places outside of the primary care doctor’s office will still be paid out of pocket or via traditional insurance. Those who want to save money and enjoy the freedom of seeing the doctor they choose by using a DPC membership should still consider some type of health insurance coverage for major illness and injury.

How can technology lower healthcare costs, increase healthcare access, and improve patient experience?

Technology is far from a panacea. It won’t solve all our problems, and in many cases, brings with it a whole new set of them. There are, however, a few key ways technology may be poised to address long-term healthcare challenges like costs, access, and patient experience.

The rise of telehealth

Believe it or not, the idea of telemedicine has been around basically as far back as the telephone itself! But for most of the last hundred-plus years, it was a niche concept that struggled with adoption.

Prior to 2020, it seemed far-fetched that doctors could accurately and safely treat patients via video calls. Even though Teladoc, one of the early industry leaders in telehealth services, has been around since 2002, telehealth was a relatively small piece of the U.S. healthcare system. Moreover, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, insurance coverage of telemedicine services was inconsistent and limited.

As it did with many other things, COVID-19 spurred an acceleration in the widespread adoption – and insurance coverage – of telemedicine. As hospitals were overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients, medical staff were at great risk of infection, and people suffering from other ailments didn’t want to visit a doctor’s office and risk exposure. Thus, telemedicine came to the rescue.

As a result of the pandemic, 22 states changed their health insurance regulations to require broader and more equal coverage of telemedicine. Greater insurance coverage was just one factor of several that contributed to dramatic increases in telehealth adoption from an estimated less than 1 percent of all care in January 2020 to a peak of 32 percent of office and outpatient visits just a few months later!

By July, 2021 research from McKinsey found that telehealth use had stabilized at a rate of 38 times higher than pre-pandemic! With telemedicine no longer a pipe dream, its potential to expand access to care in rural and low-income areas, increase appointment compliance, and reduce costs are clear. Whether this potential will materialize remains to be seen, but there are already documented benefits for both doctors and patients.

Wearable technology and biosensors

Now that patients are commonly seeing providers via phone and video, wearable tech and biosensors are a logical evolution that help doctors assess patients just like they would in an in-person office visit.

Wearable technology can range from a fitness tracker for basic activity monitoring to smart continuous glucose monitors, electrocardiograms, and heart attack detectors. Whether it’s for overall health maintenance and prevention or early detection of a serious health event, wearable health technology and internet enabled biosensors have the potential to improve patient outcomes and reduce costs by catching symptoms early – or even predicting an adverse health event before it happens!

In addition to these examples, new technology is emerging to assist virtual doctors in treating patients from anywhere like never before. TytoCare, for example, is a company that sells professional-grade medical tools for patients to use at home. Their devices transmit data directly to providers to give accurate readings and views to a telehealth provider. As technology continues to advance and give providers and patients a better virtual experience, we can expect the benefits of telehealth (like greater access and lower costs) to increase.

Artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare

We’ve written previously about AI in the insurance industry, particularly as it relates to claims processing and the consumer experience. These benefits are still very real, but that’s not all AI can do.

Artificial intelligence has the potential to:

- Identify and diagnose disease

- Provide early warnings to patients and doctors

- Enable patient/provider augmented reality

- And, yes, reduce human error and make claims processing more efficient

These capabilities are just the tip of the iceberg for smart technology’s use in the future of healthcare. It’s important to remember that AI isn’t perfect, and it’s certainly not immune from bias that can compound existing healthcare disparities. So, we’re not there yet. But that’s why this piece is the future of health insurance! The hope is, with technological advances to assist, the entire healthcare system can benefit from more efficient and less costly practices that simultaneously improve patient experiences and health outcomes.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this deep look into health insurance benefits past, present, and future. At AgentSync, we’re insurance nerds who love bringing you educational content that gives you something to think about. We’re also passionate about improving the industry for everyone who deals with the daily hassles of insurance producer license compliance. If you’re interested in being part of the future of producer compliance management, see what AgentSync can do for you.

About AgentSync

AgentSync builds modern insurance infrastructure that connects carriers, agencies, MGAs, and producers. With customer-centric design, seamless APIs, automation, and unparalleled service AgentSync’s solutions create onboarding, licensing, and appointing processes insurers and producers love while ensuring growth and compliance never compete. Founded in 2018 by Niranjan “Niji” Sabharwal and Jenn Knight, and headquartered in Denver, Colo., AgentSync has been recognized as one of Denver’s Best Places to Work, as a Forbes Magazine Cloud 100 Rising Star, an Insurtech Insights Future 50 winner, and is ranked 88 in Forbes – America’s 500 Best Startup Employers 2022.