Making cheap mainstream

Last week, we drove to chilly Portland, ME to attend ClaimVantage‘s Leadership Forum where we got to enjoy a great program Leo, Stacy, Sarah and the rest of the ClaimVantage team has put together. The event was engaging (and not just because of the throwable microphone), insightful, and filled with funny moments and Irish accents.

After Shefi’s presentation, Scott Grandmont, VP at RGAX and COO of Greenhouse, took the stage and began with the most important question: why? After 27 years in the insurance industry, Scott has seen plenty of ‘what’s’ and ‘how’s’ but now, in the age of advanced technologies and new ways of doing things, he’s looking to understand the ‘why’.

Exactly 16 years ago, at the age of 17, my friend and I launched our first business venture – selling the four species for Sukkot (one of the many Jewish holidays). Basically, we had a stand where we sold the fruit of a citron tree, frond from a date palm tree, boughs with leaves from the myrtle tree and branches with leaves from the willow tree. It was our first year in business and we were competing with merchants with bigger stands and multiple locations; occupying the best street corners. I remember walking up and down the street as other merchants began setting up their stands to check out their merchandise. I noticed that everything looked the same (which made sense since we all bought from the same wholesaler) and the only difference was price. When I got back to our stand I convinced my friend that our best strategy is undercutting our competitors, and so, our stand offered the best prices on the street and we sold through our merchandise in just three days. We were relieved and felt accomplished as our first venture was a profitable one. But a few days later, when the holiday sales were officially over, we learned that our profit was a drop in the bucket compared to merchants who kept their prices the same.

When Amazon’s online bookstore went live in July 1995, it wasn’t an overnight success. In 1996 – their first full year in business – Amazon’s best-selling book wasn’t The Notebook or Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus; it was Creating Killer Web Sites. Then, in 1998, consumers with a more conventional taste overtook the tech nerds and made A Man in Full by Tom Wolfe an Amazon bestseller. In the early days, Amazon was focused on making e-commerce mainstream by digitizing brick and mortar experiences. It introduced product reviews despite negative criticism to give shoppers the confidence they needed in an environment without sales clerks, as well as the capability to read several pages of books by digitally scanning and indexing them, delivering an offline bookstore experience online. Some consider Jeff Bezos to be the best businessman in the world, but he wasn’t considered as a ‘disruptor’ until recently, when Sears filed for bankruptcy. Instead, the modern disruptor title goes to Reed Hastings, the cofounder and CEO of Netflix.

If you’ve ever rented from Blockbuster, then you’ve probably encountered several unpleasant experiences. The most devastating one was rushing to the store to pick up a new movie just to figure out that all the copies were rented out. Then you had the late fee and the rewinding fee, and of course the actual driving to the store to pick up and return movies all while contemplating pros and cons for every transaction. Then came Netflix and introduced a new way to rent movies – one that requires an internet connection and walking a few steps to the mailbox. But it wasn’t until a year later when the company introduced the first too-good-to-be-true service – a low monthly fee where subscribers can rent as many DVDs as they want, with three movies out at a time, and keep them for as long as they like.

When Netflix launched in 1998, only 2% of American households owned a DVD player, but the company provided consumers with an offer they couldn’t resist. Unlike Amazon which focused on making shopping more convenient, Netflix delivered convenience with a cheaper price because convenience sells better if it comes with a good price tag. But despite Netflix’s early success, not everything was sunshine and rainbows. The company was losing money and in 2000, with about 300,000 subscribers, Netflix pitched itself to Blockbuster for $50 million. They proposed that Netflix, which would be renamed as Blockbuster.com, would handle the online business, while Blockbuster would take care of the DVDs, making them less dependent on the US Postal Service. The offer was declined. “We’ve studied the direct-mail model, and we continue to study it, but we still haven’t found a way to make money with it,” said Karen Raskopf, a Blockbuster spokeswoman in 2002, the year Netflix recorded a net loss of $38.6 million on revenue of $75.9 million.

Not an irrational decision at the time.

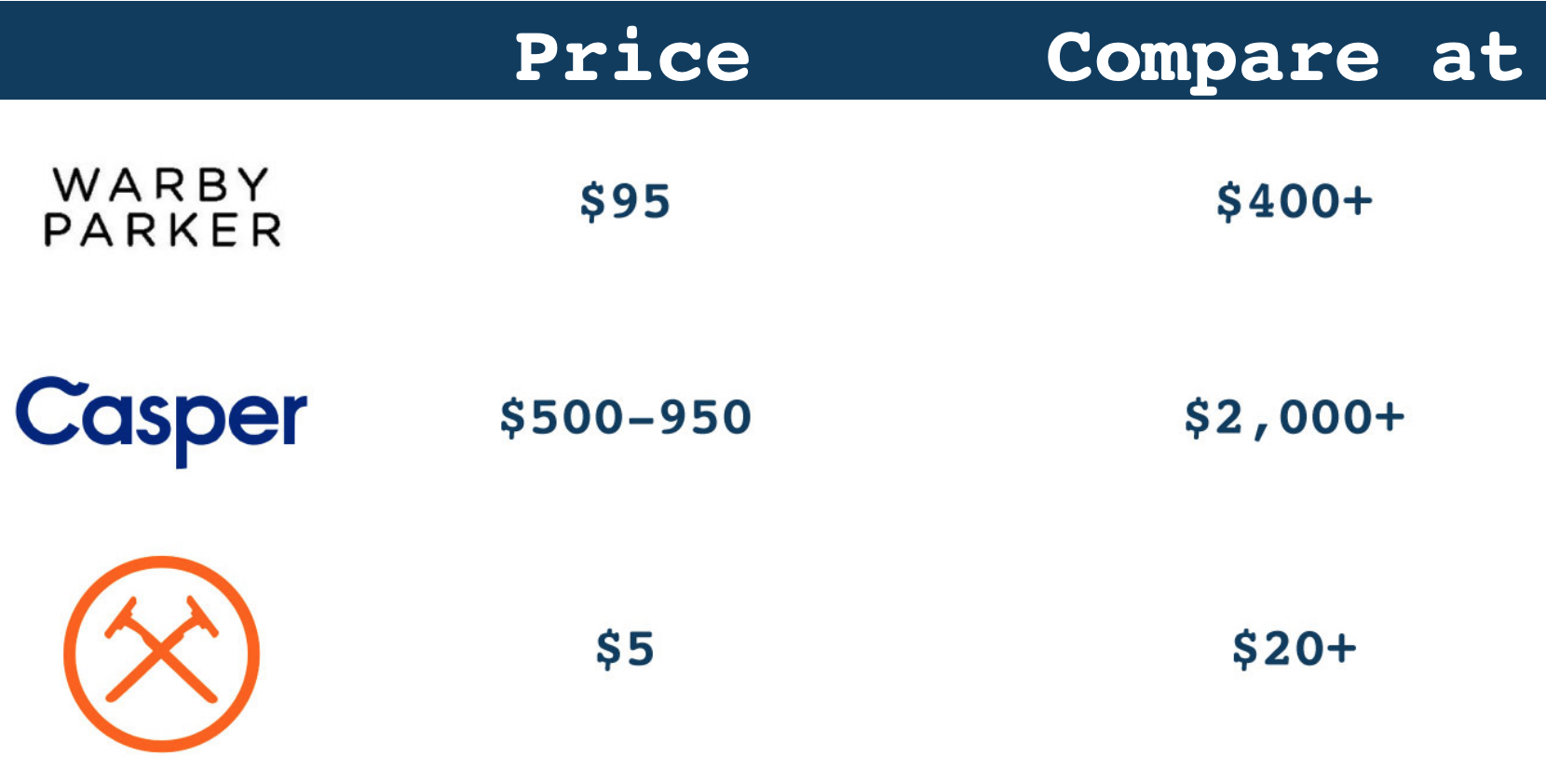

The why

In the past few years, agenda-driven consultancies wanted you to believe that ‘the why’ for disruption is customer experience. They gave you examples such as Warby Parker, Dollar Shave Club and Casper, but if you go back in time, you’ll see that it was, and is, all about price. “Why should a pair of glasses cost more than an iPhone?” wondered David Gilboa, Warby Parker’s cofounder. “Do you like spending $20 a month on brand name razors?” asked Michael Dubin, cofounder and CEO of Dollar Shave Club. “We created Casper to be a transparent mattress brand. Casper is honest about prices, doesn’t create additional SKUs to confuse customers, and doesn’t hide its business practices,” said Philip Krim, cofounder and CEO of Casper. If it wasn’t for the great price, people would be too afraid to order a mattress in a box online, even when the other option is strapping the mattress to the roof of their car while doing 60mph on the highway.

In the past few years, startup founders took a page from ‘successful’ direct-to-consumer brands and entered the finance industry. Robinhood took on Charles Schwab, Chime challenged Chase and Monzo and N26 are coming to America. These startups deliver convenience with a better price tag (or in some cases – no price at all) which typically generates a reaction from their traditional, established competitors. In June, Discover announced it will no longer charge any fees for its roughly 1 million banking customers, which can cost consumers $100 a year. “Removing all deposit account fees was an easy decision for us based on our commitment to offer the most rewarding banking products in the industry,” said Arijit Roy, vice president of deposits at Discover. Losing potentially up to $100 million a year is never an easy decision, but when consumers have a variety of better choices, Discover is left with no choice but to align themselves with the competition. And last week, Charles Schwab announced that it’s eliminating commissions for stocks, ETFs and options (currently accounting for $90 million to $100 million in quarterly revenue), making Robinhood seem less attractive.

Are you ready to pay the price?

Whether traditional brands react to their new competitors or not, today’s formula to win over the average consumer is a combination of convenience and price. In the old days people would be embarrassed to go to Chinatown to find the best deals or negotiate a better price. Now, digital brands are making cheap mainstream with their hip names and cool designs. But as we learned from the WeWork scandal, explosive growth without profits is not always enough to carry you through. So, we’re about to see VC-backed digital brands find alternative revenue streams and the insurance industry is about to pay the price, unless you believe people will go back to hailing cabs on the street, paying bank fees, and renting movies from a store.