Essentialism

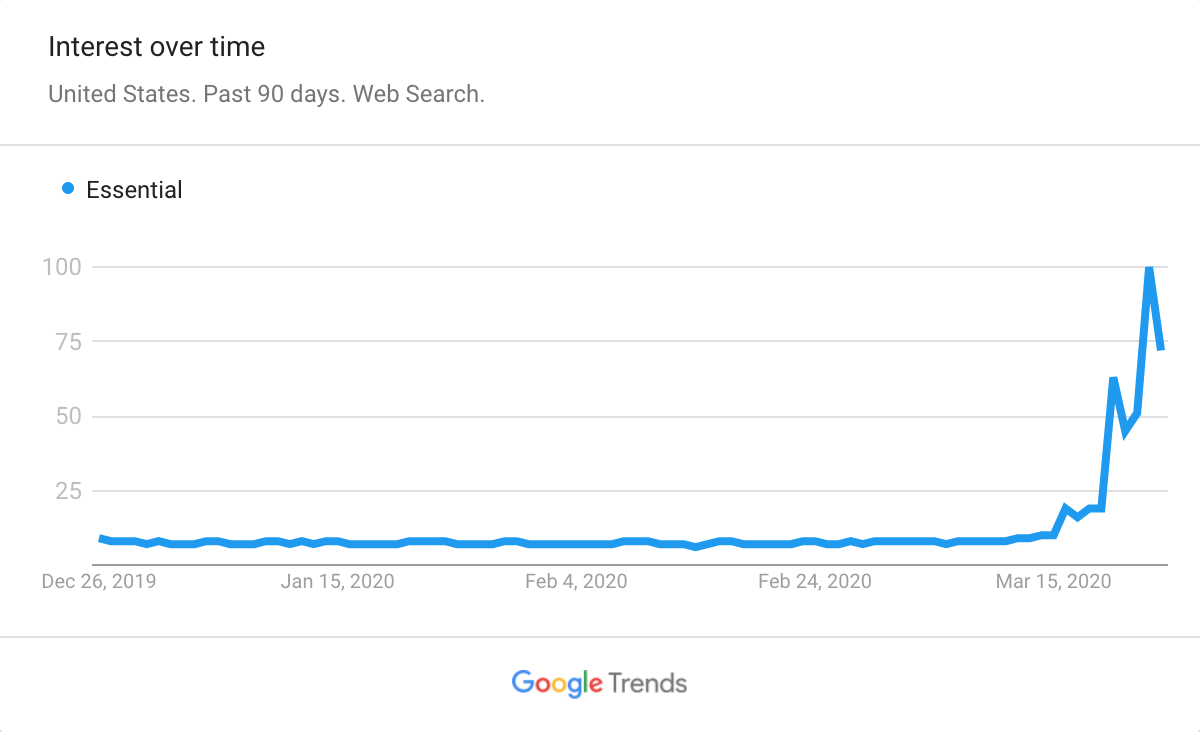

We’re hearing the word ‘essential’ a lot these days. According to Merriam-Webster, the definition of essential is “of the utmost importance.” And as most would agree, different people have different ideas of what’s important so perhaps that’s one reason why there’s a spike in Google searches for ‘essential.’

Recently, Amazon announced it is prioritizing the stocking of household staples and medical supplies over non-essential items such as flat-screen televisions and toys. As a result, Amazon Prime deliveries, which typically arrive at your doorstep in one or two days, are now showing five-day delivery promises on the lower end and a month on the higher end. “To serve our customers in need while also helping to ensure the safety of our associates, we’ve changed our logistics, transportation, supply chain, purchasing, and third-party seller processes to prioritize stocking and delivering items that are a higher priority for our customers. This has resulted in some of our delivery promises being longer than usual,” Amazon said in an emailed statement. But while one company has the power to dictate what is essential for millions, when you leave it up to the crowd, essential can be gathering outside for pasta, or going out for a run.

The recent coronavirus outbreak gave some of us a new understanding of what is essential and what is non-essential . Apparently, going to an office isn’t essential for everyone. Others (men) are realizing that with the right tools barbers are non-essential. And many parents are learning how essential teachers are. So, when the world is practicing essentialism, it’s worth looking at insurance from an essentialist’s point of view.

Greg McKeown is an essentialist. The New York Times Bestselling author of Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less, discovered an interesting insight. “What is it that holds capable driven people from breaking through to the next level? And the answer to that question to my great surprise is success. I first observed this working with executive teams in Silicon Valley where I noticed that when they were focused on a few things, it led to success. But success breeds so many opportunities and options that defuse the very focus that leads to success in the first place and so exaggerating the point in order to make it, I found that success becomes a catalyst for failure.”

According to McKeown, focus leads to success which leads to options, and options can take you down two different paths – either greater success or total chaos. You could say that, as a whole, the insurance industry is focused and successful. With a BIG RED F for innovation (selling online isn’t innovative, it’s essential), and despite a few exceptions such as American Family acquiring Networked Insights or on-demand insurance, the majority of players are sticking to what has made them successful and that’s building their businesses on the backs of agents or increasing advertising budgets. So, if we go by McKeown’s approach, we could say that most insurers are essentialists, yet somehow the industry is filled with non-essentials.

I recently met an executive of an insurance comparison site who told me that a certain large carrier isn’t willing to work with them despite working with others in their space. The reason, he said, was because the carrier believes they are doing right by consumers by actually allowing them to compare quotes, unlike other comparison sites they work with that just generate leads. Companies like GEICO and Progressive aren’t dumb; they know conversion rates suffer when their lead-gen partners give consumers the runaround. But this is one essential ingredient of their strategy to maintain control instead of becoming a rectangle with a logo and price tag on a comparison site, leaving it up to consumers to decide. The other essential ingredient is being everywhere all the time – online and offline, display and search. EverQuote is not an essential part of the insurance value chain – it can disappear tomorrow and consumers would still be able to get insurance. But EverQuote is an essential piece for companies like GEICO and Progressive for two reasons: They are getting more consumers to shop for insurance online and skip agents, and agents who cave in and buy leads from EverQuote are wasting their limited resources to play a game they can’t win. But there’s a third reason. EverQuote’s model gives a bad name to other comparison sites which leads some shoppers to forget their fantasy of comparing real quotes in real-time and just go back to the basics – getting quotes from familiar companies, and GEICO and Progressive are familiar. Essentially, GEICO and Progressive are willing to bleed a bit by enabling the likes of EverQuote so their competitors bleed out.

Clearly, GEICO and Progressive aren’t the only companies enabling non-essentialists for the sake of their essential needs. In the past few days, agents who are members of a popular insurance Facebook group kept asking if their services are deemed essential. Often times, people confuse their operation with their line of work, and while insurance is essential, having hundreds of thousands of agents at the office or prospecting offline is not. Having motivational rallies for thousands of commission-based agents is non-essential. And having an Assurance IQ employee whisper tips to seasoned agents to seal the deal while on the phone with shoppers is non-essential.

Then there’s Erie that showed the industry just how quickly essential elements become non-essential either due to opportunism or genuine concern for the “security and future” of families, following their announcement that customers can obtain life insurance without a medical exam. “During these unprecedented times, we want our customers to feel confident in their family’s security and future. In addition to doing our part to help mitigate the spread of the coronavirus, we understand the availability of paramedical exams may be limited in the coming weeks due to the temporary closure of ‘non-essential’ businesses in many areas of ERIE’s footprint,” said Louis Colaizzo, senior vice president of Erie Family Life.

Coming from the advertising industry, I’ve always wondered how advertising began. Here’s my theory: Advertising was born from a need to sell non-essential products. In advertising, they teach you that there are two kinds of purchases: emotional and rational. It doesn’t take a lot of creativity to advertise a rational product like insurance; a simple 15 minutes could save you 15% or more on car insurance will do. On the other hand, getting folks to do non-essential tasks such as upgrading their smartphones every year requires sophistication.

There aren’t many products with the benefit of being rational products, yet this rationality is the main contributor to the many non-essential parts the insurance industry currently holds on to. When you’re selling a rational, universal product in a paper form, greatness isn’t essential. And when greatness isn’t essential, the barriers to entry are low and you end up with a crowded market.

Essentialism is a controversial topic. For McKeown, practicing essentialism isn’t about surviving with the essentials; it’s about doing less, but better, and he was intrigued by an insight. “Almost all the literature that’s ever been written about success is about how to become successful. And almost none of the research and almost none of the literature is written about what to do once you are,” he noticed. Still, you can’t ignore the fact that another definition of essential is necessary, and necessary has its limits. These limits can be the number of necessary employees following your investment in automation or other processes that eliminate a need you once had.

For a company, being essential is being selfish. The amount of money GEICO and Progressive spend on advertising, which is essential for their success, is reducing the number of employees they need and/or making the product more expensive for consumers. Cutting lead-gen sites out of the equation won’t hurt insurance shoppers, but it will hurt the folks working for such companies. And yet, we’re at a period when people are assessing what’s essential, which will cause insurance companies and others to do the same, and Root and JPMorgan pausing hiring for the time being is just one example.

As more companies with strong distribution capabilities enter insurance, and as more insurers embrace technology, there will be a reduction in the number of non-essential insurance elements. But this isn’t the time to discuss the future. Now is the time to discuss the present, and while experts are divided when it comes to the financial impact of the coronavirus, there’s no doubt that the image of some insurers and agencies will be damaged given the fact that some businesses are discovering, to their surprise, that they aren’t covered.

Lemonade says insurance is a social good but companies like Assurance IQ make me skeptical. Then again, Prudential (the owner of Assurance IQ) just donated 153,000 protective face masks and respirators to the state of New Jersey. A while ago we published a paper to our research members titled The Part-Time Insurance Agent (which we are now making available to everyone) that explores a new concept for selling insurance. Here’s a piece from the report that I believe is relevant than ever: “The part-time insurance agent concept can also be applied in the real world. Insurance companies can have their employees volunteer to support local businesses such as restaurants and bars. In return, customers visiting these places will be made aware of their insurance affinity.”

Aside from the social aspect, you might just discover that selling insurance full-time isn’t essential for success.