COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Suicide Rates and Risk Factors

Written by:

Scott Rushing, Vice President and Actuary, Head of Risk and Behavioral Science, Global Data and Analytics, RGA

Erin Crump, Vice President Business Initiatives, RGA

As the third anniversary of the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic approaches, determining the full impact of its many ripple effects remains years away.

From education to the economy, wellbeing to the workplace, many short- and long-term implications of this unprecedented global disruption are only beginning to surface.

For life insurers tasked with determining potential mortality impacts, navigating the pandemic’s many unknowns presents an ongoing challenge. It requires a thorough understanding and analysis of the data, coupled with a vigilance in tracking and incorporating new information as it becomes available.

This article explores one of the many areas impacted by the pandemic: suicide rates and suicide risk factors. Review of the data elicits the following conclusions:

- The pandemic has impacted mental health globally, including suicide.

- While certain risk factors are elevated, evidence does not indicate an increase in the incidence of suicide globally.

- Evidence from U.S. insurance data suggests an overall reduction in suicides during the first year of the pandemic; however, additional data indicates that suicides increased among young populations during that same period, particularly among adolescents.

- The full effects of the pandemic continue to unfold, and data is still emerging.

- Insurers should continue to monitor outcomes and be alert to any increases in suicide or contributing risk factors.

- Preventive measures and efforts put in place during the pandemic should be maintained.

Global Suicide Rates During the Pandemic

According to a study from The Lancet, global suicide numbers remained largely unchanged or even declined for upper-middle and high-income countries in the early stages of the pandemic. The study focused on comparing April-July 2020 to a trendline from the previous 12-15 months. Results indicate reduced suicides for most countries early on, despite reports of increased episodes of depression, anxiety, and suicidal thinking.1

While the study has clear shortcomings, including measurement of only a short time period (for both trendline and observation period), low numbers from some countries, and the inability to stratify results by age, sex, and other factors, the overall decline in suicides across multiple countries is significant. So, why did suicide rates improve even amid the disruption and stress of the pandemic? Potential factors include:

- Countries increasing mental health services

- Community support expanding and households being together more

- People reducing everyday stress by staying home

- Fiscal support initiatives buffering economic stress

It is important to note that some of this decrease in suicides was likely temporary, which is supported by data from Japan. There, monthly suicide rates declined by 14% during the first five months of the pandemic (February to June 2020). By contrast, rates increased by 16% during the second wave (July to October 2020), with a larger increase among females (37%), and children and adolescents (49%).2

Reduction in Suicide Rates in the U.S.

In the U.S., a more sustained trend emerges, based on a series of public studies developed through an ongoing collaboration among RGA, LIMRA, the Society of Actuaries (SOA), and RGA subsidiary TAI. The studies analyze U.S. industry data to quantify excess mortality resulting from the pandemic.

One of the studies focuses on cause of death and provides extensive analysis of claims filed for 16 causes of death, including suicide. The study, which includes data from 31 companies comprising nearly 3 million death claims from individual life policies from January 2015 through March 2021, provides a unique view of the pandemic’s impact on suicide rates for insured lives. The analysis shows suicide trends for standardized cohorts by three age categories and gender. Figure 1 presents results for one of those cohorts: males under 40.3

Figure 1: U.S. suicide rates for fully underwritten males under 40

First quarter results, 2015-2021

Source: SOA 2022 Cause of Death Report

Age-standardized mortality rates for this cohort show suicide rates during the pandemic significantly below the pre-pandemic trendline. For all male cohorts, most quarters in the pandemic fall below trend. While results for female cohorts are less consistent, more quarters fall below trend than above. The overall conclusion: Insurance data strongly suggests a reduction in suicides during the first year of the pandemic in the U.S.3

It is important to note that additional data indicates that the stresses of the pandemic may have contributed to an increase in suicides in younger populations in the U.S., particularly among adolescents. One study of 14 states identified an increase in the number of suicides among youth 10 to 19 years of age and in the proportion of youth suicides compared to the overall population. With suicides among adults 35 and older declining, these findings suggest the pandemic may have affected youth differently than adults.4

COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Suicide Risk Factors

While suicide rates in countries such as the U.S. may show improvement in the short term, evaluating the potential impact of the pandemic on suicide rates moving forward must take into account the increased prevalence of certain suicide risk factors, such as mental health disorders, alcohol consumption, and opioid and drug use.

Mental Health

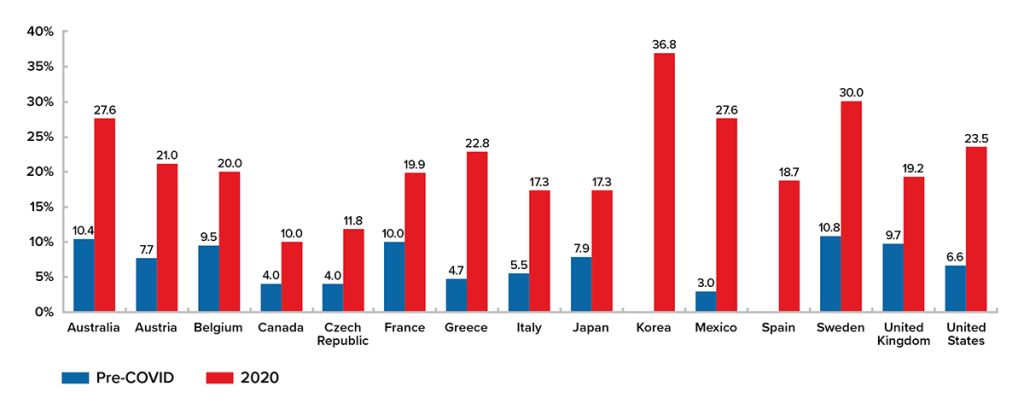

One of the key risk factors for suicide is a history of mental illness or psychiatric disorder. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the COVID-19 crisis has led to a significant and unprecedented worsening of population mental health. Figure 2 compares the prevalence or symptoms of depression in early 2020 and a year prior to 2020. The data consistently shows that rates of depression increased in 2020. Similar results were observed in anxiety.5

Figure 2: Prevalence of depression increased significantly in 2020

National estimates of prevalence of depression or symptoms of depression in early 2020 and in a year prior to 2020

Source: OECD, Tackling the mental health impact of the COVID-19 crisis: An integrated, whole-of-society response

In many countries, prevalence of depression in early 2020 more than doubled compared to prior years. Periods with the highest reported rates of mental distress correlated with periods of intensifying COVID-19 deaths and strict confinement measures.5 The World Health Organization reported that in the first year of the pandemic, the prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by an estimated 25% globally.6

Alcohol Consumption

A strong association exists between alcohol misuse – either chronic or acute – and suicidal thoughts, attempts, and death from suicide. Based on studies in multiple regions, approximately one in four deaths by suicide involve alcohol, either as the primary cause (e.g., intentional alcohol poisoning) or as present in the person’s body at the time of death. Alcohol use disorder is the second-most common mental health disorder in people who have died by suicide. People experiencing suicidal ideation are seven times as likely to attempt suicide when drinking heavily.7

Data from some countries shows a significant increase in alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the U.S., for example, as stay-at-home orders began in the early part of 2020, one market insights firm reported a 54% year-over-year increase in national sales of alcohol for the week ending March 21, 2020; online sales increased 262%.8

A survey study featured in the Journal of the American Medical Association compared self-reported drinking behavior before and during the pandemic in a U.S. population. Increases during the pandemic were observed in nearly every measure, especially in women. On average, three of four adults consumed alcohol one day more per month. For women, there was also a significant increase of 0.18 days of heavy drinking, from a baseline of 0.44 days – an increase of 41% over baseline. Women also had an average increase in the Short Inventory of Problems (SIP) scale of 0.09 over the average baseline of 0.23, representing a 39% increase, which is indicative of increased alcohol-related problems independent of consumption level.8

Drug and Opioid Use

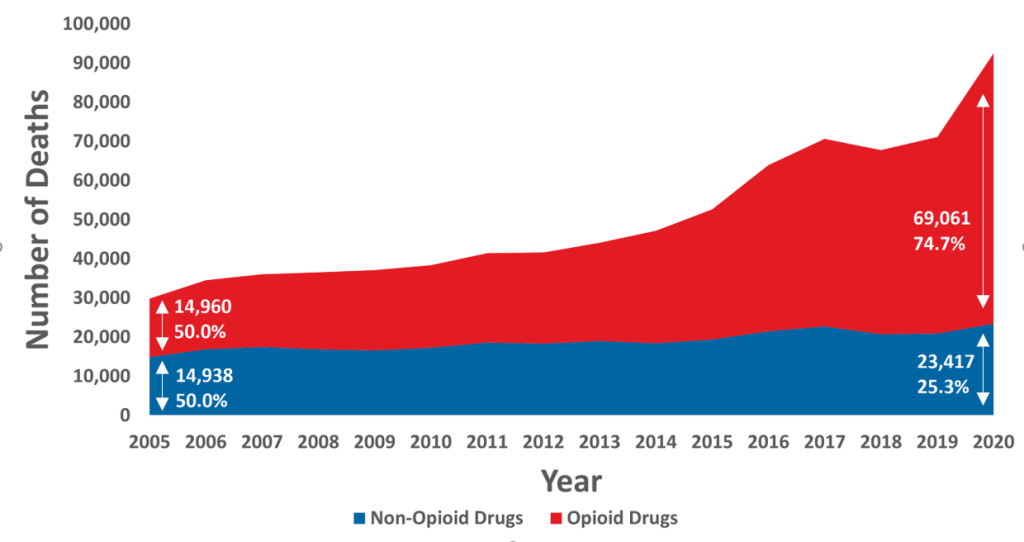

As with alcohol consumption, problematic drug use brings an elevated risk of suicidal thoughts, attempts, and death from suicide. And as also happened with alcohol, drug use increased during the pandemic.

In the U.S., reports show drug use has surged since the onset of the pandemic: Positive screens for fentanyl, cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine have all increased from previous years.9 In Canada, a study on self-reported use revealed more drug users engaging in riskier drug-using behavior, such as re-using syringes or using alone. In addition, some respondents indicated they had relapsed during the pandemic.10

The increase in drug misuse in the U.S. contributed to a rise in overdose mortality in 2020. Opioid-related deaths, which were on the rise for more than a decade before leveling off between 2018-2019, were much higher in 2020 than in previous years. The peak in May 2020 coincided with social isolation measures early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Fentanyl and synthetic opioids experienced the largest spike – nearly doubling from January 2020 to May 2020.11

Figure 3: U.S. and Annual Drug Overdose Fatalities

Source: RGA analysis of mortality data from MCOD, Epidemic within a Pandemic: Opioid Misuse and Mortality Risk through 2020

It is important to note that this graph shows all drug overdose fatalities, which is not the same as suicides, as many overdoses are unintentional. About 5% to 7% of overdose deaths are recorded as intentional.12,13 Because it can be difficult to determine intentionality, the actual numbers are likely higher. Regardless, this trend is alarming, and important to monitor from a suicide perspective given the known connection between substance use and suicide risk.

Conclusion

While suicide is not the only indicator of the negative mental health effects of the pandemic, there was not an increase in deaths by suicide in the first year of the pandemic. The story is far from over, however, and monitoring emerging data is essential as the pandemic’s full health and economic consequences continue to unfold. Vigilance in tracking trends will help detect any increases in suicide or contributing risk factors, and perhaps provide a better understanding of what has kept suicide numbers down to date.

Preventive measures enacted during the pandemic should be maintained to help ensure people continue to receive necessary support and to help prevent longer-term detrimental health impacts. New measures to specifically serve young people must also be developed and implemented, as evidence suggests this population may be particularly at risk and in need of tailored support. This includes steps taken by governments, employers, and healthcare providers – as well as (re)insurers. At RGA, for example, we have partnered with medical groups and local agencies to promote suicide awareness and prevention and have conducted life design sprints focused on finding ways insurers can contribute potential solutions.

We believe the insurance industry has a significant role to play – via its unique combination of resources and expertise – in suicide awareness and prevention. As historical data has proven and the COVID-19 pandemic has magnified, suicide rates can change much more rapidly over time when compared to most medical causes of death. This suggests that intervention strategies, including any championed by the insurance industry, could help mitigate global suicide rates moving forward.

References

1. https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S2215-0366%2821%2900091

2. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-020-01042-z

3. https://www.soa.org/resources/research-reports/2022/cause-of-death/

4. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/newsroom/news/042722-COVID-adolescent-suicide

5. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1094_1094455-bukuf1f0cm&title=Tackling-the-mental-health-impact-of-the-COVID-19-crisis-An-integrated-whole-of-society-response

6. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1

7. https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Alcohol-Use-and-Suicide-Fact-Sheet.pdf

8. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2770975

9. https://nida.nih.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2021/the-federal-responses-to-the-drug-overdose-epidemic

10. https://www.camh.ca/en/camh-news-and-stories/increased-substance-use-reported-during-covid-19

11. https://www.rgare.com/knowledge-center/media/research/epidemic-within-a-pandemic-opioid-misuse-and-mortality-risk-through-2020

12. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/suicides-drug-overdose-increased-among-young-people-elderly-people-black-women-despite-overall-downward-tren

13. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/danvergano/drug-overdose-or-suicide